It is 7am at Naotcha Primary School in Blantyre where deadly mudslides displaced thousands from the slopes of Soche Mountain last month.

Some 2 200 displaced people occupying the public school are just waking up in classrooms that house 120 people, twice the count of learners they are supposed to sit.

However, the children, whose schooling has been disrupted by the disaster, cannot step out to play on the slippery, muddy grounds outside the overcrowded rooms. Inside one of them, about 20 are singing, playing and reciting what they used to before some schools were turned into camps for the homeless population.

In the classroom occupied by 127 children and 19 mothers is Deborah Simao, 14, who was living with her uncle when tragedy struck.

The guardian went missing when the longest-lasting cyclone ripped the hillside location, now the worst-hit spot in the 14 southern districts.

“My burning desire to learn and become a nurse looked achievable last year when my uncle came to Chikwawa to pick me up so that I could come to learn in town, but all that has been shattered by the cyclone struck,” she laments.

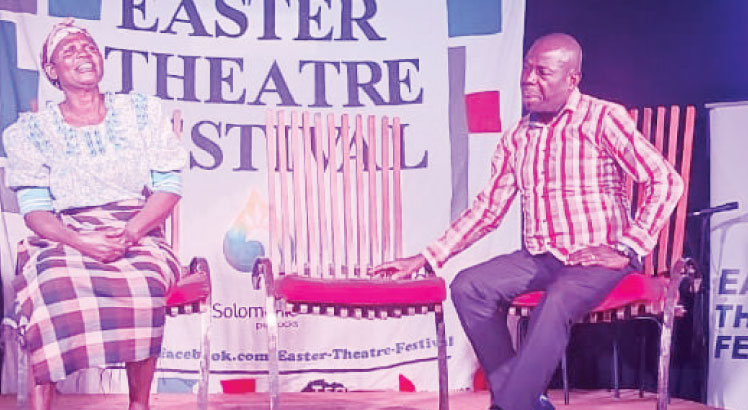

Children sing and play joyfully at Naotcha camp in Blantyre

Deborah put up at her friend’s house the night mudslides killed dozens in Mkanamwano and Kharika settlements in Chilobwe Township.

Every morning, the Standard Seven girl wakes up early and paces across the camp hoping to overhear “some good news” about her missing uncle, a bricklayer.

She explains: “Uncle John Ben was a bricklayer, my pillar and only hope.

“He took me in upon seeing that my parents, who separated a long time ago, weren’t adequately supporting my education. Where do I go from here?”

Her uncle is among 527 persons reported missing following the disaster, with 564 000 displaced, 676 confirmed dead and 918 injured.

Playing in circles creates safe spaces for children like Deborah to forget their agony, make friends and share smiles, she states.

“When we meet to play, we forget every problem, encourage each other to face the future with hope and remind each other what we used to learn before schools were suddenly closed,” she explains.

Grace Kamanga, 42, one of the mothers who care for the displaced children in her block, admires the children’s tenacity and defiance in the eye of the devastating storm.

Her house collapsed on the tragic Sunday around 10am, forcing her to flee to Naotcha Camp.

The mother of three explains: “These children are going through a lot, but children are just children: they love to play, make friends and make merry.

“When they meet, they only share smiles, yet some have lost their homes, parents, guardians, siblings, clothes, blankets, books, uniforms, pens and other basics.”

The children affected by Cyclone Freddy need urgent support the children to recover from the loss and damage, states Kamanga.

“Due to water and sanitation problems, some have not taken a bath since they came a week ago,” she explains. “Toys, games and educational materials can also help spice up children’s daily play in anticipation for their uncertain return to school, states the caregiver.

The severe cyclone forced the Ministry of Education to close schools from March 13 to April 17 2023.

Unicef is supporting the Government of Malawi to relieve the hardship faced by affected children, including the provision of schools-in-a-box kits and child-friendly corners for continued play and learning.

Naotcha headteacher Lawrence Msaleni says Standard Eight boys and girls preparing to sit primary school leaving examinations in May are the worst hit by the school closure.

He states: “The pressure on the school is immense as schooling has come to a stop since we have offered all 27 classrooms to people displaced by mudslides and floods in surrounding areas.

“The 4 510 children who used to learn in three shifts are now stuck at home or in camps, including Standard Eight learners who were supposed to start sitting mock examinations from 29 to 31 March when all classes were supposed to close for Easter holidays. Clearly, their preparations for national exams will be negatively affected.”

But Deborah says the loss of school days is not less biting for children in lower classes who were supposed to start sitting end-of-term examinations.

“We lost months at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, another month in the second wave of the pandemic in 2021 and a week when schools in Lilongwe and Blantyre delayed opening due to the ongoing cholera outbreak. Without such disruptions, I would have been in Standard Eight or Form One,” she states.

The post Children just being children first appeared on The Nation Online.

Moni Malawi

Moni Malawi