Every health facility guarantees its surrounding population access to quality care within reach, but Gladys Enoch returned home gutted on a stormy Friday when her one-year-old baby had high fever.

The woman with the baby on her back could not hide frustrations as she exited Phalombe Health Centre, which was flooded amid Cyclone Freddy last month.

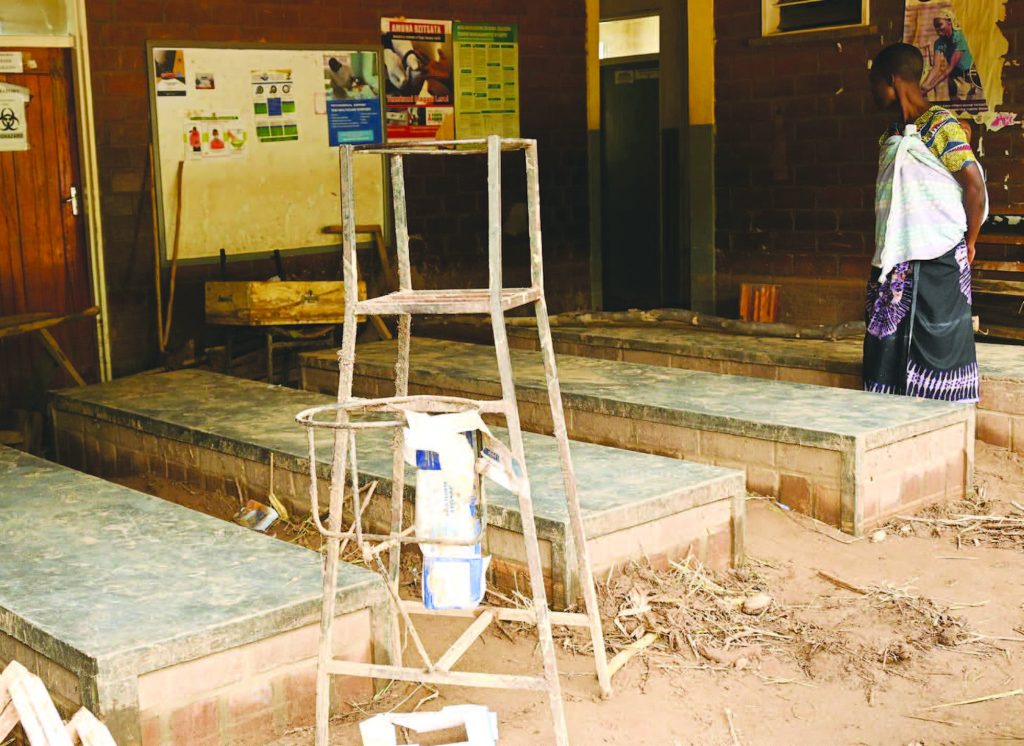

Gladys hits a blank wall during her hospital visit to forget

“My son Honesty’s body temperature rose dramatically the previous night. He has been shivering and vomiting, but we are going home without any assistance because the health centre has been closed due to severe flooding,” she narrated, calming the weeping baby.

Gladys’ setback personifies the plight of about 52 000 people who depend on the devastated health facility, where community members were seen clearing knee-high silt using shovels, hoes and wheelbarrows.

Nearly six health centres in Phalombe were hit hard by the rainstorms, floods and mudslides that disrupted service delivery in 95 life-saving facilities nationwide.

The flood soaked all rooms alongside medicines, patient’s files, furniture as well as resident health workers’ homes at Phalombe Health Centre, now closed indefinitely following the devastation.

Now a security guard watches over the soaked remains in mud-filled rooms, with a health surveillance assistant signalling patients to the nearest healthcare centres.

Now patients and pregnant women endure extra costs to travel about five kilometres to Holy Family Catholic Hospital where those without referral letters pay. Others make a 15km trip to Phalombe District Hospital, where a return trip costs about K3000, enough to buy three meals for Gladys’ family of five.

She lamented: “We are suffering untold hardship due to the disruption that followed three days of relentless heavy rains.

“With no health workers and medicines in sight, I have to choose between buying un-prescribed medicine from a local drugstores and going to the distant hospital. This drains the money I can use to feed my family.”

The path of destruction is vivid from Mulanje Mountain in the vicinity, where the floods and landslides wiped out people and invaluable property in Bokosi Village.

The tragedy left the health workers overwhelmed by bodies and injured persons as the health centre was closed “because the environment is no longer favourable for their life-saving work”, says district director of health and social services Dr Sam Sibakwe.

The medical doctor explains: “Had you come on a normal working day, you would have found 100 to 150 people waiting for care in the outpatients’ department, no less than 10 pregnant women waiting to give birth in the labour ward, five to 10 with newborns on their beds, some 200 people waiting to receive HIV treatment and 70 women with children aged below five waiting to get routine vaccination and nutrition screening.

“But all this suddenly stopped when Cyclone Freddy struck the facility.”

According to Sibakwe, the busy health facility serves more than 50 000 people in the vicinity, including the worst-hit Bokosi, where mudslides from Mulanje Mountain in the vicinity ripped homes in its way.

The devastation was terrifying, Sibakwe explains.

“All services have been disrupted because the floodwater, debris and mud from the mountain destroyed everything. Even the displaced health workers are traumatised having lost their property and suffered injuries,” he explains.

The halt has pushed patients and pregnant women into financial hardship due to long travels to nearest facilities and medical bills outside the public healthcare system.

“We have a service-level agreement with Holy Family Mission Hospital, but our patients require a referral letter to get assisted free of charge. Sadly, the health workers who issue, sign and stamp the letters are not available because their houses are no longer habitable,” Sibakwe says.

The community health worker on standby redirects about 35 people a day, including those who cannot afford travel and medical costs elsewhere.

Children aged below five are highly affected due to disruptions in routine immunisation, nutrition checkups and other services offered during their specialised clinics, according to Sibakwe,

UNICEF has supported the Ministry of Health to roll out mobile clinics and transport for health workers to help them reach vulnerable communities with health services.

Sibakwe explains: “We are under pressure to reopen the health centre, but it will not be easy. This is a daunting task and the price is huge.

“We have to clear the debris, renovate the buildings and procure new furniture and replenish medicines and medical supplies,” he says.

Thieves looted doors, frames, mattresses, trolleys, buckets and other supplies from the devastated health centre.

Sibakwe says more mobile clinics would mitigate the long wait for restored services by bringing services closer to the affected communities.

“Health services have been paralysed, so we call on partners to support us to provide mobile and static clinics close to affected communities. We need more clinicians, nurses, community health workers, vehicles, fuel and medical supplies so we can go to places hit hard by the disruptions caused by the cyclone,” he says.

And Gladys hopes her most trusted health facility will reopen soon.

“The longer the reopening of the facility, the more people will die of treatable diseases at home, the more pregnant women will give birth without the help of skilled hands and children will miss on vaccines that protect them from preventable deadly diseases.

The post Cyclone cripples health services first appeared on The Nation Online.

Moni Malawi

Moni Malawi