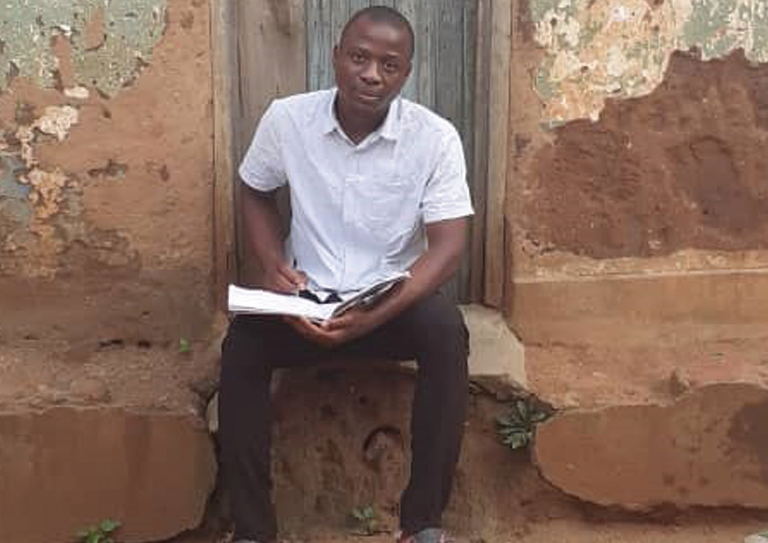

Fredson Binda is the first person in a family of seven to make it to university. In 2019, he was selected to Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (Luanar) City Campus as a generic Bachelor of Science in Gender and Development student.

A self-boarder in a cracked tiny house in Area 22 in Lilongwe, the second-year student sits in a dark room with dust swirling in sun rays trickling in through a milky window.

Binda: My parents cannot afford much

His face is filled with emotions as he details his financial problems, including lack of tuition fees and upkeep after his benefactor stopped supporting him last year.

“This has left me in imminent danger of being withdrawn from the university. My parents cannot afford much,” he says.

Binda’s parents are small-scale farmers in Nsanje. They find it tough to support his education.

As examinations approach, Binda has only paid 11 percent of the semester fees. He does not know where the balance will come from.

Meanwhile, his landlord has also threatened to evict him from the house worth K7 000 monthly.

Due to the piling financial pressure, he used to skip lectures to sell boiled eggs in the Capital city.

One day, the Lilongwe City Council patrol team confiscated his merchandise for vending in undesignated places. This reduced Binda to a beggar.

He leaves Area 22 every morning with a briefcase full of letters, some written and stamped by Luanar, to beg for support from wellwishers. Binda has distributed the letters to various companies.

Meanwhile, the time dedicated to his academic work keeps dwindling. During the visit, he had attended only 17 of the 36 lectures in the semester.

City Campus student welfare envoy Joel Ndalama says: “Binda is one of many needy students in this predicament. Some withdraw from the university on financial grounds yearly.”

In an interview, Higher Education Loans and Grants Board committee spokesperson Dr Henry Chingaipe said Luanar City Campus ineligible for the public bursary scheme because it is an income-generating initiative.

He said: “The campus is neither a public nor private university. This makes its students ineligible for loans from the board because they are admitted on the basis that they have the ability to pay for their studies without recourse to public funds or support.

“That takes them out of the pool of eligible students. The loan fund supports generic students.”

Ironically, students from profit-making institutions such as private and faith-based universities with higher fees receive 50 percent of support from the public bursary scheme.

But Luanar marketing and communications manager Bessie Milanzi questions Chingaipe’s justification for denying City Campus’ needy students educational loans.

She says the campus is duly accredited and enrols undergraduate generic students.

Milanzi says: “There is no official statement from Luanar that City Campus is a commercial entity.”

“The board’s argument is that City Campus is seen as commercial, yet it is heavily subsidised by the government.

“They say that the actual cost of training a City Campus student is over K4 million while one pays K800 000 per year. Luanar finds the argument the board uses to deny students loans to be impaired.”

But Chingaipe counter-blames Luanar authorities, saying the board uses information provided by the universities.

Luanar management, he says, stated that the campus follows a business model where students have the capacity to pay economic fees.

“The bottom-line is that all undergraduate students admitted to public universities in ways other than the National Council for Higher Education’s selection are not eligible for loans,” says Chingaipe.

Civil Society Education Coalition executive director Benedicto Kondowe says the board is doing injustice to the Luanar City Campus students.

He urged the board to formulate and enforce strict measures to recover loans that have matured.

On his part, Educationist Dr Steve Sharra said the students’ loans board was formed from “a narrow definition of who is eligible or not”.

He said: “The City Campus case is an anomaly. It doesn’t matter whether the campus is subsidised. Given the current state of our economy, K800 000 is a lot of money for the average Malawian.

“If the policy really is like that, then it calls for a revision because the reality on the ground is that many City Campus students are withdrawn annually.”

In the 2021/22 academic year, the loans board financed 95 percent of the applicants though it admits that “the amounts given were not sufficient”, especially for students’ upkeep and private institutions.

Almost 99 percent of applicants from the University of Malawi accessed the loans, with about 97 percent from the Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences, 93 percent from the Malawi University of Science and Technology as well as Mzuzu University (Mzuni).

According to Mzuni Student Union president Cephas Anjiru Maganga, about 245 applicants were left out of both upkeep and tuition fees support, while 315 were only provided with tuition fees.

He says: “The 95 percent by the board is not something to celebrate as many students may have been left out.

“Already, about 132 have reserved places at Unima and we are bargaining with the Mzuni administration to consider the 400 students on compassionate grounds as they are on the verge of being withdrawn over fees balances while about 31 have completely withdrawn. We are also engaging the loans board to revise their eligibility criteria.”

The post Needy students stuck in hell appeared first on The Nation Online.

Moni Malawi

Moni Malawi